Has Ohio lost its labor force edge?

Aug 21, 2014On Friday August 1, the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) released its national jobs numbers for July. The report contained a familiar narrative: a modest increase in total employment and a slowly declining unemployment rate. However, because the unemployment rate is calculated as a fraction of the labor force (those who are employed or actively seeking employment), it does not accurately reflect the percentage of the total population that remained unemployed. That number remains stubbornly stagnate. The BLS estimates that only 59% of the U.S. civilian (16 years and older) population was employed in July, only one percentage point higher than in June 2011, the low point of the last 30 years. The employed to population ratio remaining steady as the unemployment rate drops can be explained by the declining labor force participation rate, a problem Ohio shares.

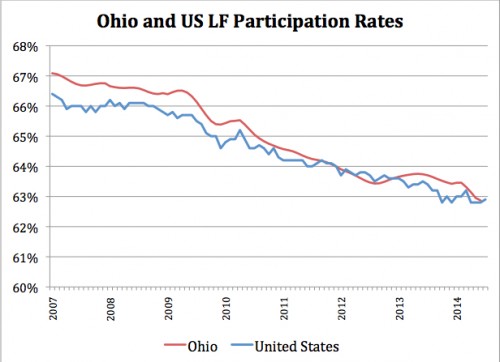

In July 2014 less than 63% of Ohioans aged 16 and over declared themselves to be part of the labor force. This is lower than in any month since October 1978, before women had fully entered the workplace. Traditionally, Ohio has exceeded the national average, but the gap has disappointingly closed over the last few years. In particular, 2014 has seen a steep drop, with more people dropping out of Ohio’s labor force during the months of March, April, and May than in any other three-month span since the height of the recession in October 2009. Similar to the United States as a whole, here are three major reasons for the declining labor force in Ohio:

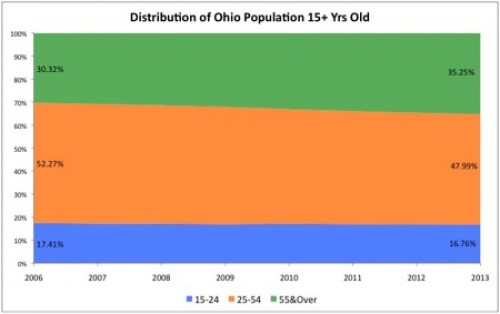

Demographic changes: An aging population results in a natural decline in available workers. The graphic below is based on a combination of U.S. Census and American Community Survey data and illustrates the changing age demographics of Ohio between 2006-2013.

According to the BLS, in June 2014 about 54.7% of people in the U.S. aged 16-24 participated in the labor force, compared to 80.9% of people aged 25-54 and 40.0% of people 55 and over. Ohio has seen over 4% of its 15 and over population shift from 25-54 into the 55 and older segment over the past 7 years. Similar demographic changes are happening all around the country. According to some estimates, the changes account for about 25% of the nationwide labor force decline.

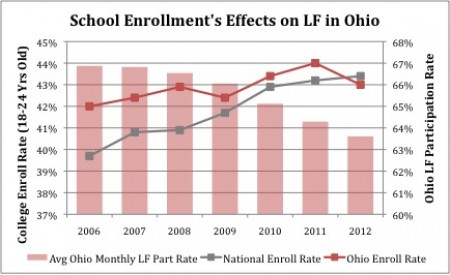

School Enrollment: When the economy dips and the job market suffers, the opportunity costs associated with school enrollment decline and the perceived necessity of greater education rises. More potential workers return to school to complete a degree (or add one), and a higher percentage of teenagers complete high school. This effect is illustrated below by the percentage of Ohioans aged 18-24 who were enrolled in college between 2006 and 2012. Data is from the American Community Survey with the Ohio labor force participation rate overlaid.

Higher school enrollment causes a temporary decline in the labor force. However, in the long run it creates a better educated and more productive and efficient labor force. The bad news for Ohio is college enrollment rates did not rise as dramatically as the rate of the nation, likely meaning much of Ohio’s labor force reduction has come from a third major factor.

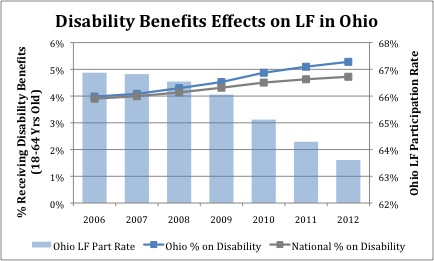

Increased Disabled Beneficiaries: Since the Great Recession, disability claims have skyrocketed, and unfortunately Ohio has outpaced the national average in this category. The worst news is that unlike school enrollees, people claiming disability insurance rarely return to the labor force.

Between 2006 and 2012, Ohio’s population aged 18-64 saw almost no change, but in 2012 there were over 93 thousand more disabled beneficiaries within that age range. With disability claims rising to all-time highs, policymakers will need to confront reform. The Social Security Disability Insurance trust fund is projected to be empty by the end of 2016.

Ohio may have lost its historical edge on the nation in labor force participation rate among its population. In order to counteract that Ohio will need to attract a younger generation into the state, or face the challenge of increasing production among a permanently smaller and continually aging labor force.