You Say Tomato, I Say Tomahto: Differences in Ohio’s Tax Collection Estimates

Apr 05, 2019Governor DeWine’s budget proposal highlighted his policy agenda for the next two years—increased funding for at risk school-aged children, a new fund to protect Ohio’s water, and investments in programs to help local governments combat the opioid epidemic are just a few of the new initiatives the governor is proposing.

Thankfully, the governor decided against any new income or business taxes that could harm Ohio’s families and the state’s economy. However, all of the administration’s initiatives come with a large price tag. And the question remains—how does the governor plan to pay for all this?

It appears the administration is relying on an overly optimistic view of growth in tax revenues.

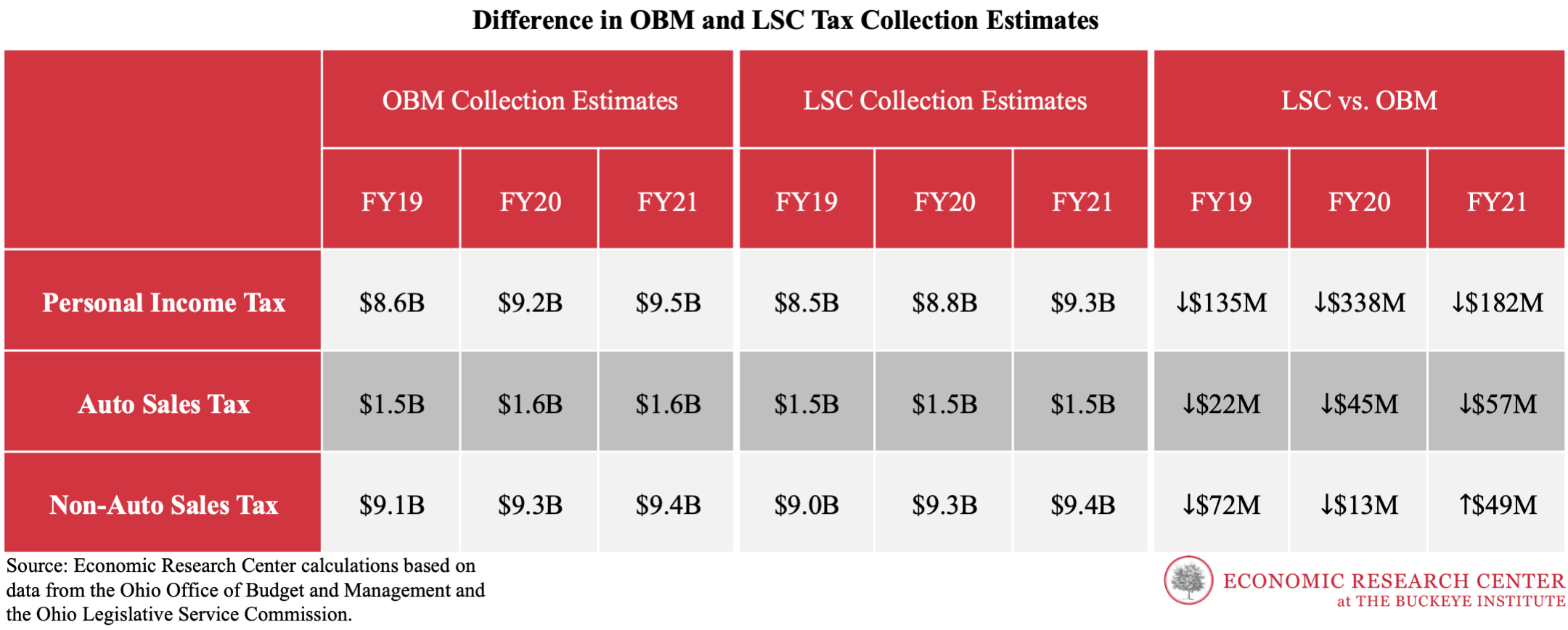

In the administration’s proposed budget, the Office of Budget and Management (OBM) expects to collect $23 billion in taxes for Fiscal Year 2019, $24 billion in FY2020, and $24 billion in FY2021. However, when the Legislative Service Commission (LSC) released their Forecast Book, they projected that Ohio would collect a decidedly lower amount in taxes—more than $600 million less through FY2021.

Both the OBM and the LSC projections used economic forecasts from IHS Markit, a widely known economic forecasting firm. But there are notable differences in how these broad-economic indicators were used in forecasting the amount of taxes the government will collect. And as LSC Commissioner Mark Flanders commented, LSC expects Ohio to collect less in taxes this year than OBM expects, which affects the current debate on Ohio’s biennial budget and its revenues.

The biggest difference between OBM and LSC comes in the amount of personal income taxes each expects the state to collect. LSC predicts Ohio will collect nearly $519 million less in personal income taxes than OBM over the next two years. Even starting from OBM’s estimates for this year, LSC would expect Ohio to collect $231 million less in personal income taxes than OBM over the next two years. In general, OBM expects Ohio’s collection of tax dollars to grow faster than LSC, implying that OBM is painting too rosy of a picture, which will hurt Ohioans if spending cuts have to be made or taxes increased later.

The problems associated with predicting tax revenues isn’t new. A look at past tax collections shows us there are large fluctuations in collections from year to year. In fact, during Fiscal Year 2009, tax collections fell by about 8.5 percent from estimates as we were hit with the Great Recession, but when the state began to come out of the recession, collections grew. Even today, we continue to see differences between estimated tax collections and actual collections, which illustrates how difficult it is to predict tax collections over the next two years.

While some make look at the differences and see it like the song Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off, this is not an issue of simply looking at the estimates differently. And the difficulty in predicting tax collections is why The Buckeye Institute has urged policymakers to avoid large spending increases over the next two fiscal years. If an economic downturn occurs, Medicaid costs rise, and revenues don’t grow as expected, policymakers will be forced to make deep and painful cuts as they had to do in the early 2000s or burden Ohio’s families and businesses with new taxes to cover revenue shortfalls.

As we recommended in Sustaining Economic Growth: Tax and Budget Principles for Ohio, spending increases should be tied to the growth in population and inflation, and any additional spending increases should be coupled with spending cuts in other areas. Furthermore, surpluses— like the one OBM expects for this fiscal year—should not be squandered on new spending, but rather, they should be saved to combat any future economic downturns or returned to Ohio’s taxpayers through permanent tax rate reductions.

Andrew J. Kidd, Ph.D., is an economist with The Buckeye Institute’s Economic Research Center.